“They called this mission impossible. It was not supposed to be able to happen. We were the team that was able to make it happen.”

― GWS Senior Vice President

In 2017, a large urban public school system made national news for its closing and consolidation plan. They needed a partner to manage the project with white glove service – and they also wanted to hire primarily local labor.

In 2017, a large urban public school system made national news for its closing and consolidation plan. They needed a partner to manage the project with white glove service – and they also wanted to hire primarily local labor.

This project was significant: it touched 123 schools, and affected 30,000 students. The consolidated schools crossed over gang lines; beyond the typical worry of furniture instillation by the first day of school, there were serious concerns about safety – especially given the recent trend of violence in the city.

The following is the story behind the story, as told by a GWS Healthcare Senior Vice President:

“We worked with various community groups – including the Urban League, Catholic Partners, staffing agencies, and local job fairs – to hire people to move furniture out of the schools that were closing. We reached out to a local church who mentored people wanting a second chance, and hired 40 people who worked with us the entire time. We went from zero employees to 764 employees very quickly, and all of them were from the local community.

We had to train everyone on furniture from scratch. We set up training centers in unoccupied schools, broke people into teams, and talked about the process that we were going to follow. We could only train about 60-80 people at a time, so we had to schedule it carefully so we could have everyone ready at the right time.

At one particular school, we were working with people from two rival gangs. On the first day of work, it was tense; we had to separate them by floor. We could have completed the project that way, but it didn’t feel right. That night, we brainstormed how we could get them to work together. We came up with the idea of creating a human chain from the building to the truck, where we had people from the rival gangs alternating all the way down. That way, everyone had to work just as hard as the next person, and they had to receive and hand-off everything – desks, chairs, and so on – from a person that they formerly hated. And it worked. We had zero incidents.

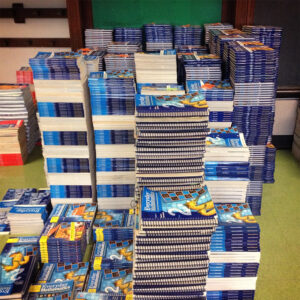

One of the coolest things we did was the resource sale. We took all of the books and other educational resources left behind in the 50 schools that were closing, and consolidated them into one school. Teachers and curriculum directors could come and shop the sale. We even built a web site where they could shop online, and we kitted what they ordered for easy pick-up or delivery. It cost us $4.5 million to do this, but we were able to give $2.5 million back to the schools.

One of the coolest things we did was the resource sale. We took all of the books and other educational resources left behind in the 50 schools that were closing, and consolidated them into one school. Teachers and curriculum directors could come and shop the sale. We even built a web site where they could shop online, and we kitted what they ordered for easy pick-up or delivery. It cost us $4.5 million to do this, but we were able to give $2.5 million back to the schools.

There was also a significant amount of IT equipment left behind, too. We competed with – and beat – a well-known computer company to manage this part of the job. We logged and redeployed 25,000 assets, and they were all working on day one.

Outside of the buildings themselves, we assembled what we called “SWAT Teams” that moved around the schools to beautify them. They picked up trash, replaced lights, and painted cross walks. And people from the community came out to help. It really was a group effort. The community owned this project.

There’s one thing in particular that I will never forget about this project. We built a command center, and the COO of school district, who was a former colonel in the Marine Corps, ran it. We checked in with him on the first day of school, and he said, ‘It’s eerily quiet today.’ There were no issues. None.

It’s unbelievable what we were able to accomplish there. Unbelievable.”